Share This Short Story

I was ten years old when I started wearing glasses. It would have been much earlier, but I was missing the point of eye tests.

To explain this, you first need to understand that academics came easy. My first few years of school consisted of near perfect scores on all tests.

As strange as this sounds, I remember the first word I misspelled on a test – carrot. I spelled it with one r. I was horrified – also with two r’s. My friend sitting beside me laughed that I didn’t know how to spell it because I knew how to spell everything. He was six, so you have to take that claim with a grain of salt.

Or maybe not. The next word I remember misspelling was extraordinary. Third grade spelling bee. Eighth round. There was a collective gasp when the teacher said, “Wrong.” Not that I am scarred – also with two r’s. Just please don’t offer me an extraordinary carrot for dinner or I might have a psychotic break.

As much as words clicked for me, numbers were magical. Johnny has two apples. Mary gives him three apples. How many apples does Johnny have? All my friends were counting on their fingers (well, several of my friends were busy picking their noses), but the number 5 just instantly floated into my brain.

I also wanted to know how much per apple Mary charged Johnny. A dime an apple equals 30 cents. Yes, it was clear in the first grade that I was going into finance. A cold, hard capitalist six year old.

I can’t explain how it came so easily. I hated being told I had to show my work. I would look at a problem and the answer appeared like a vision. When I had to show my work, I would work backwards to create the steps. To this day, I rarely use a calculator.

But there is just one slight challenge – academic prowess does not exactly move you up the exalted public school social strata. At the very pinnacle of the social pyramid of public school are the cool kids. They have a certain natural social grace and charisma. What they don’t exhibit is a natural ability to do long division in the third grade. Amazingly, that talent is not much appreciated.

The popular kids could throw a baseball or catch a football. I couldn’t do either one. Still can’t. The only sport in which I excelled as a kid – bowling. Not exactly hot with the cool kids.

And to prove exactly how geeky I am, I was good at bowling because it can be explained very mathematically. Seriously. It is basically one giant physics problem. You have velocity (how fast you roll the ball), friction (how dry the lane is), spin (revolutions of the ball), angles (the angle at which the ball collides with the pins) and inertia (the pins). Anyone who bowls regularly will tell you that bowlers do not aim at the pins – they aim at the arrows about 15 feet down the lane (called dovetails) and adjust based on the factors I noted above. Sadly geeky I know, but the following graphic – which I did NOT create – proves I am not alone with approaching bowling as one giant math problem:

Yes, that is right. That graphic comes from a website dedicated to the physics of sports and other common interests. The mere fact that I even know such a website exists should cement my geek status.

Bowling is hardly the only sport that involves a lot of math, as that very website proves. Any good football quarterback or soccer striker understands a great deal about velocity and angles and resistance. They just happen to look much cooler doing it.

The other big difference in bowling is that your opponent can’t touch you. Sure, they can taunt you. They can steal your nachos. But they can’t touch you. And, until they invent full contact bowling, it is still a sport that allows you to do the math without fear of pain.

Back in the academic world of elementary school, I might not have been overly popular for acing every test. But, weirdly, everyone expected me to and, thus, I would take more ribbing for missing a test question than for getting a perfect score. Strange dynamics, but the more I achieved perfect test scores, the more pressure I put on myself.

Which brings me to eye tests. I was ten years old when my pediatrician discovered I couldn’t see very well. He wanted me to take a peripheral vision test, a test I had never seen and thus had never prepared for. All I had to do was look through a viewfinder and follow the bouncing red ball with my eyes.

Confidently, I leaned forward and stared into the whiteness of the screen. He waited a few seconds and spoke, “You can start when you are ready.”

“Ready.”

“Just follow the little red ball with your eyes.”

“Sure.”

We sat for a few more seconds until the doctor said, “Go ahead, you can start.”

“Ok. Whenever you want to start the red ball.”

Confused, he asked me to lean back. He looked into the machine and then looked back at me. “Go ahead and look through the viewfinder again.”

I did.

“Now follow the red ball.”

I waited for the red ball to appear.

He told me to lean back and wrote something on a piece of paper. He held it up. “Read this to me.”

I tried to lean forward.

“No, from there.”

I just shook my head. Who could possibly read something from that far away? He was sitting at least five to six feet away.

He moved the clipboard slowly toward me. “Just read this aloud when you can.”

Seconds before the clipboard bumped my nose, the words came into focus – “Can you read this?”

He sat back, surprised.

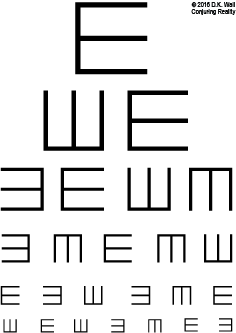

He pointed at a white spot on the office wall. I knew what it was. It was the same thing in the school office where they took us once a year for an eye test – a Tumbling E Eye Chart.

“Which direction does the E face on the sixth line?”

“Up, Right, Up, Left, Down, Right, Left.”

“Correct.” After a slight pause, he asked, “Can you see the sixth line?”

“No.”

“Then how do you know the answer?””I memorized it.

“I memorized it.”

“Why didn’t you tell anyone that you couldn’t see it?”

“No one asked.”

Yes, that is correct. Every single year, every student was traipsed through the nurse’s office at school to take the eye test. You entered through a door right beside the eye chart and waited on your classmate to take the test. That wait was just long enough for me to memorize the chart. Then I entered the room, walked to the far end, and rattled off the directions of the E’s on any line they asked. Like everything else, this was a test. And tests must be passed.

With my doctor revealing my newfound eye test results, my parents whisked me to an ophthalmologist who diagnosed me the same way eye doctors have every since – my eyes are perfectly healthy; I am just extremely nearsighted. A few days later, I had brand new glasses on my face.

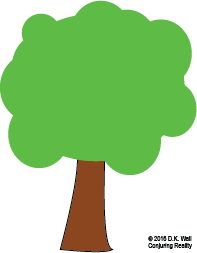

My father was driving me home and I was gazing out the window. Dad asked what I was thinking and I answered, “Holy cow, you can see the individual leaves on the trees.” You know how you draw trees when you are a kid:

I honestly thought that was what they looked like. Well, actually, I thought they were giant green blobs on a brown blob. I was amazed to discover that you could see individual branches and leaves. My father was not quite as amused.

The next day in class, I discovered that you could read what the teacher wrote on the board without having to walk close to it on the way out of the classroom. And catching a baseball was amazingly easier when you could see the ball coming directly at you – rather than waiting for it to hit you.

So I told you earlier about remembering misspelling carrot and extraordinary. I have another great memory from shortly after receiving my glasses.

We were at recess playing kickball. As always, I was playing deep, deep, deep right field where no one could possibly kick the ball. Weirdly, my classmates always thought I was most helpful in that position. I watched – with great clarity through my new glasses – as one of the best athletes in our school stepped up to the plate – Patrick Hall. With his athletic prowess, I am sure the next few seconds are not in his memory because of his sports accomplishments to come. There would be no reason for him to remember it.

But I sure do.

The kickball rolled toward him. His foot connected perfectly and the ball sailed high in the air, floating well above the heads of all of my classmates. Only I stood between Patrick and his usual home run. The difference for me was that I could see that bright red ball dropping from the sky, a newfound discovery. Ignoring the collective groan from my more athletically inclined classmates, I positioned myself directly under the ball. It hit me solidly in the chest just as my arms wrapped around it.

And the cheer went up. Patrick glared, stunned.

The geeky kid had caught the ball.

Support The Musings

Call it a tip. Or the euphemestic "Buy me a coffee." I prefer patronage. Generous patrons have supported artists throughout history. Whatever you want to call it, if you enjoyed this post, consider making a donation to help offset my costs. Your support will help keep my stories ad free. Click here to make a contribution of any amount.