Share This Short Story

My best wishes and thoughts for everyone dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey and facing the onslaught of Hurricane Irma. Mine is but a story of inconvenience and it pales in comparison.

Friday, September 22, 1989 – The window glowed with the early light of dawn. Fearing I had overslept, I looked for the clock – purchased because its large illuminated numbers saved me from having to find my glasses in the middle of the night – but the face was blank. The power was out.

Sitting up, I searched the bedside table with my hands until finding my glasses. With vision restored, a glance at my watch revealed I was not late. A busy workday loomed in front of me, calls with our plant managers in Puerto Rico who were to provide new damage assessments from the devastation of Hurricane Hugo just four days earlier. And discussions with our logistics teams as we struggled with the closure of the Port of Charleston, closed by the same hurricane.

Opening the blinds, I watched a lone car maneuvering around fallen branches and leaves on the ring road of the massive apartment complex. A swimming pool sat in the center of the property, surrounded by a ring of buildings, then the road, and, finally, a second ring of outer buildings. We lived in the front corner in one of the outer buildings in an apartment facing the interior, effectively muzzling the road noise from the busy avenue outside the complex’s security wall.

The car continued beyond our apartment, turned toward the main avenue, and disappeared from view. A few seconds later, he backed up, turned around, and drove back into the complex. “Poor guy. He must have forgotten something,” I mumbled.

“Or maybe some branches are blocking the exit.” I followed the pointing finger and saw sizeable limbs laying across the manicured lawns and on top of cars.

Fearing for our own cars, we raced out onto our small deck with a wider view. Our cars, parked undamaged just below us, were mercifully covered only in leaves. Right beside them, however, lay a massive pine tree, uprooted in the winds. My unobstructed view of the parking lot from the bedroom had always been partially blocked by that tree and I hadn’t even noticed.

That tree wasn’t the only one uprooted. Multiple large pine trees leaned against buildings across the way, many snapped liked twigs despite their size. In fact, finding undamaged trees was virtually impossible. Every tree I could see seemed to have suffered significant harm.

The night before, we had watched Forty-Eight Hours, a popular newsmagazine, live from Charleston, South Carolina, as Hurricane Hugo came ashore. As the show ended, I turned off the light with the confidence that Charlotte, 150 miles inland, would only see a little rain and a little wind, just like had happened dozens of times before. Surveying the chaos outside, however, I began to suspect that Hugo had caused far more problems inland than anyone had predicted.

A second car worked its way through the littered road toward the entrance. We watched as he disappeared around the corner of the building, only to return a few seconds later. What was preventing people from leaving?

“Think some branches are down across the entrance?”

I nodded. “Probably. I guess we should go clean them up so we can get to work. Maintenance probably won’t get here for a while.” I motioned toward the broken trees and damaged shingles. “And they are going to be busy cleaning everything up.”

We pulled on jeans, walked down the flight of steps and outside, chatting as we rounded the building to clear the debris from the entrance. Were we going to be late to work? Was there more damage in the city?

Passing the corner of the building, the secured entrance came into view. We stopped cold.

The solid wood fence that surrounded the complex transitioned to wrought iron just before the entrance road. A landscaped median separated the entrance road from the exit road. A guard shack sat in the median. The look of a secured entrance discouraged those who didn’t belong, but the reality was that the front gates were never closed. And no guard ever sat in the guard shack. Everything was for appearance only.

And, on that morning, we were grateful for the lack of a guard because the guard shack was crushed. Three giant oak trees had fallen across the entrance, stacked on top of each other and reducing the shack to splinters. Moving the trees was out of the question; we couldn’t even see over them to the avenue. And, as apartment dwellers, we had no need to own chainsaws.

We looked at each other, surprised by our find and enveloped in silence. I strained for any sign of the normal rush hour traffic clogging the road outside. “I don’t hear any traffic,” I said.

“Nope. Nothing.”

“How can that be? It’s the start of rush hour. Should be bumper to bumper out there.” I stared at the fallen trees and made a decision. “I am going over.”

“What? Are you crazy?”

I shook my head. “I’ve got to see. It’s not that high.” I started to climb, scraping and scrambling over the massive trunks. When I finally reached the peak, I stood as high as our second-floor balcony. Startled at what I saw, I dropped to the other side.

Central Avenue is a major artery in Charlotte. Two lanes of traffic in each direction, normally traffic clogged from commuters inching toward downtown.

Today, it sat empty. Not a single car moved. The road was littered with branches, leaves, trashcans, newspapers, and other unidentified garbage. Most unusual, in the middle of one of the lanes, was a traffic light.

Laying on its side, the lights dark, it would be an unimaginable hazard if a car did pass. I decided I should move it to the side of the road, helping the next poor person driving down the road.

I walked across the empty lanes, the silence eerie in its absence of vehicles. As I reached the yellow frame, I was first struck by its size. Until that moment, I had never thought about how large a traffic light was, but it was huge. Each single light was about a foot in diameter. Adding in the aluminum frame, the light was nearly four feet long and about eight inches deep.

Checking to make sure it was not connected to any wires, I deemed it safe to drag out of the way, but when I grabbed hold of it, I realized its mass. The entire traffic light weighed around fifty pounds. The metal screeched across the asphalt as it dragged it to the curb.

Just as I rolled the massive light onto the sidewalk, another realization hit me. Every morning, I cursed the left turn to exit our complex because we didn’t have a traffic light. I had to wait on the light a half block away to turn to hope for a break in traffic.

This light had not simply fallen from its mounting; it had been blown at least a half block away. I was sweating from dragging it a few feet, and Hugo had effortlessly tossed it around like paper.

That realization finally allowed me to truly see around me. Telephone poles broken like toothpicks. Trees snapped in half. Debris blocking the roadway. No lights, no radios, no electricity for miles. I was standing in a modern American city – miles from the ocean – without any modern conveniences.

I crossed the empty street, climbed over the fallen trees, and returned to our dark apartment. The wait for normalcy to return had begun.

Our electricity came back five days later, much earlier than many of my co-workers. For weeks, National Guard troops directed traffic through intersections since virtually every traffic light in the city was dark. And the City of Charlotte lost an estimated 80,000 trees.

We were the lucky ones. Hugo was barely a Category 1 hurricane when it crossed Charlotte, being declared a tropical storm just a few miles north of the city. But we were a city not expecting 100 mile per hour winds. And not built to withstand it.

The news coverage rightfully focused on the heavily damaged Charleston.

But the small town of McClellanville, SC, just north of Charleston was the epicenter of landfall, nearly destroyed by a 16-foot tidal surge. The high school that served as an evacuation center flooded six feet deep as terrified residents stood all night on furniture to stay above the water. Amazingly, all 400 residents of the fishing village survived. A small plaque at the high school is placed at the high-water mark – above eye level.

If you are in the path of Hurricane Irma, please take it seriously. And if you were affected by Hurricane Harvey, our thoughts are with you.

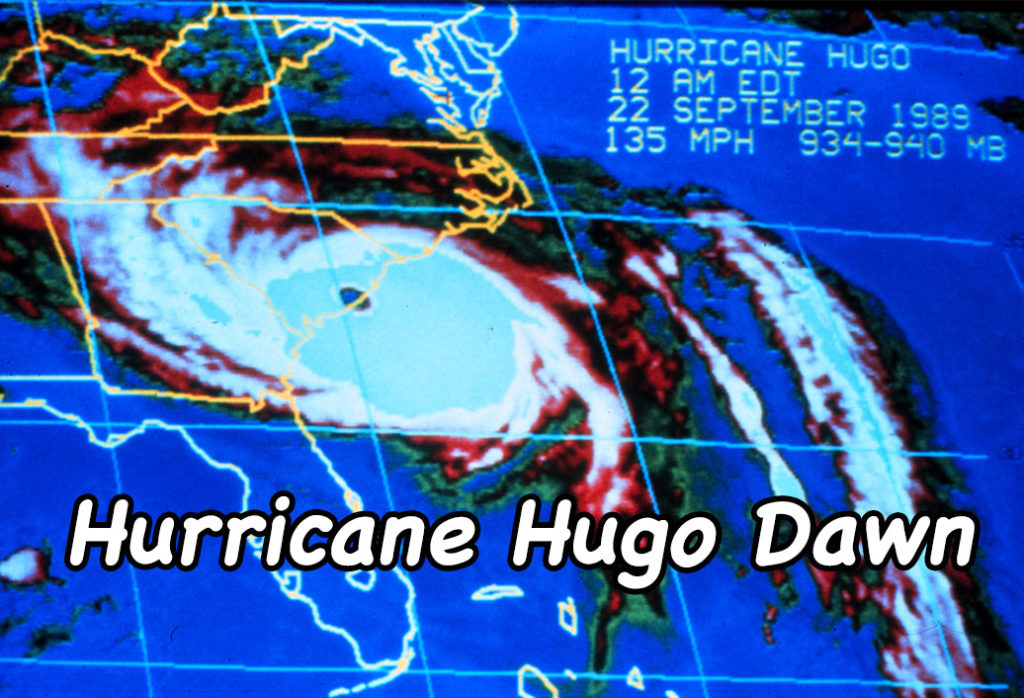

Today’s featured image, courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce, is an enhanced infrared imagery of Hurricane Hugo the morning of September 22, 1989, as the eye is over the coast near Charleston, South Carolina.

Support The Musings

Call it a tip. Or the euphemestic "Buy me a coffee." I prefer patronage. Generous patrons have supported artists throughout history. Whatever you want to call it, if you enjoyed this post, consider making a donation to help offset my costs. Your support will help keep my stories ad free. Click here to make a contribution of any amount.

Hurricane Hugo, boy what a mess that was!!! That was one heck of a way for my 21st birthday to come in.

It is frightening to remember what a Cat. 1 hurricane was capable of doing that far inland and now knowing that Hurricane Irma could possibly come our way… with her power… everyone take this seriously.

Loved your story. We were at ground zero for Sandy (Ocean County NJ). I prepped 7 days prior just in case. With 3 dogs and 2 adults, we all huddled and slept on the first floor which I elevated in 1992 as a result of the flooding eith the Perfect Storm. Instead of a 3 block foundation, I opted for another couse. We survived with minimal damaged, no heat, electric, and water for 4 weeks! That

Included heating bricks on the bbq keeping us warm at night and snuggling the dogs at night on the couch. We have since moved to the Eastern Shore of VA and out of the flood zones!