Share This Musing

The City of Asheville and the surrounding communities are slowly flickering to life, but the road to recovery continues to be long.

Over 100,000 homes were damaged, many destroyed. Major roads remain impassable, some potentially for years. Piles of debris line our streets and will take months to haul away. About 95% of the residents of Asheville again have running water, but it’s not potable. We will have to boil water to drink for several more weeks.

The biggest loss, of course, has been life. Currently, North Carolina has attributed 98 deaths to the storm—34 by drowning, 23 in landslides, and the rest from falling trees or other storm-related causes.

But how did a hurricane do this much damage so far inland? The answer, of course, is somewhat complicated. It wasn’t a single thing, but a combination.

Full Disclaimer

To be clear, I am not a meteorologist. Or geologist. Or a hydrologist. I am, quite frankly, not an expert at all.

What I am is a writer who loves the North Carolina mountains who also geeks out over the weird weather patterns we have. Take what I’m saying with a grain of salt. I’ll do my best to explain.

Hurricanes are weird beasts

My couple of years of coastal living taught me a great deal of respect for these monster storms, but my education began long before. Prior to Helene, my worst experience was living in Charlotte during Hurricane Hugo back in 1989.

The most critical thing to understand about hurricanes is that they are both predictable—and wildly unpredictable. The best way to describe them is they wobble. Those neat spaghetti lines don’t show how they shift 20 miles this way and 40 miles that way as they march forward.

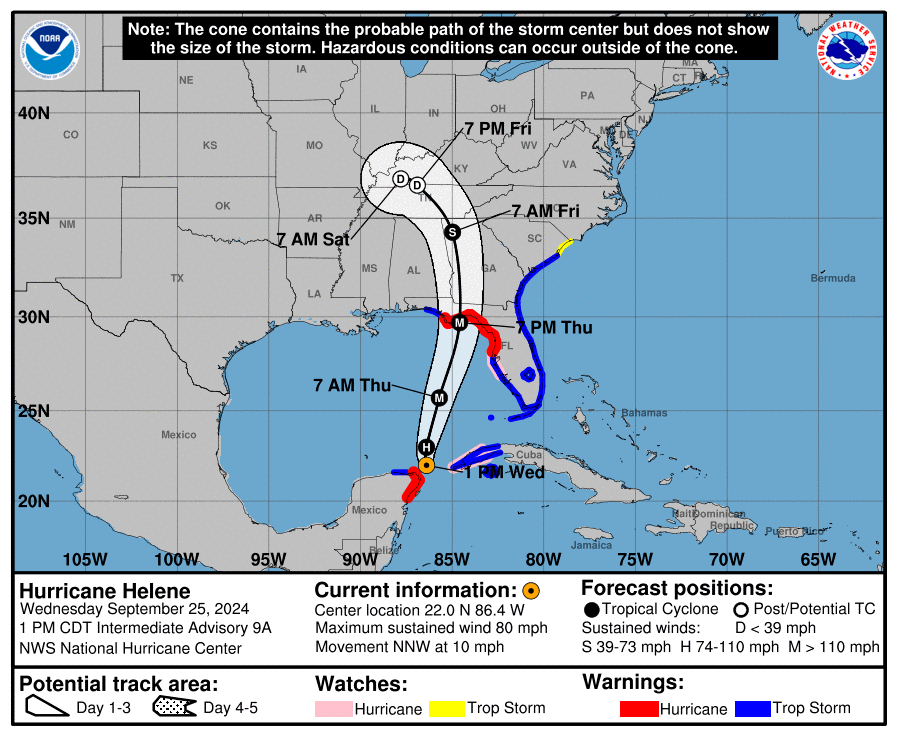

Though scientists have become quite skilled in tracking and predicting their paths, it’s not perfect. That famous cone of uncertainty is probably the most misunderstood chart. That center line is not an exact predicted path. Rather, the whole shaded area is the most likely path of the center of the storm.

The power of the storm spreads for hundreds of miles. Because it spins counter-clockwise, the worst section is to the right of the eye. Thus, even on Wednesday, they were predicting the storm would pass to our Southwest bringing us the strong right side into the mountains.

As Helene wobbled and weaved, her center ended up shifting east and coming much closer to us. Her mighty right side lined up perfectly and slammed against the mountains rising to meet her. In short the predictions of her path were accurate, but with enough wobble to spell disaster for us.

Aren’t hurricanes unusual so far inland?

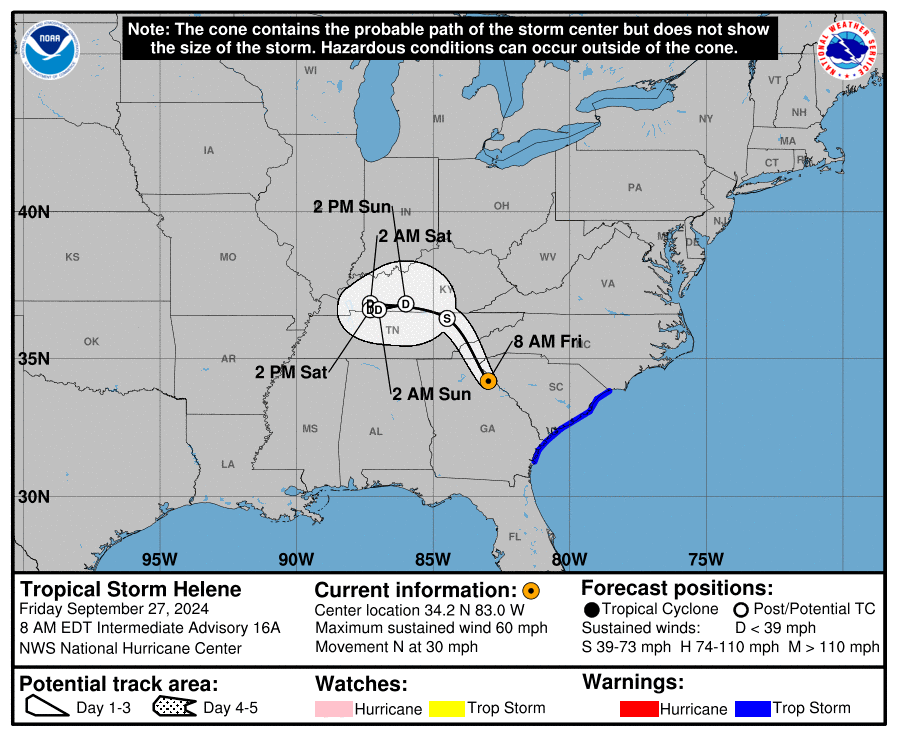

Yes… and no. Helene, to be clear, was no longer a hurricane when she spread her path of destruction across us. Remaining a hurricane so far inland would be very unusual.

But a tropical system is not out of the ordinary. We are quite accustomed to the remnants of a hurricane still packing a punch when they reach us. In a way, we almost welcome them. September and October are typically quite dry, so the remnants of some storm give us much needed rain to avoid a deadly forest fire season.

So, sure, we expect one or two of them. Sometimes, though, they are too strong despite our distance from the ocean.

Tropical Storm Fred in 2021 probably doesn’t strike too many memories, unless you lived in the community of Cruso. A flash flood of the East Fork of the Pigeon River came out of its banks with almost no warning and killed six.

The “big one” for most of us—at least before Helene—came in 2004. Hurricanes Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne all crossed our paths that September. The results were catastrophic.

Almost as bad was the “Great Flood” of 1916, long enough ago to be only a tale heard from ancestors. Two July tropical systems hammered our region setting modern-day records. Photos of the disaster can be spotted around town.

Even less well known was the granddaddy of them all, a 1791 disaster whose records are sketchy, but establish the all-time high-water marks, all puns intended.

Helene beat them all.

Why weren’t we warned?

To be clear, we were. Mostly. In the days leading up to Helene, the message was clear. This could be as bad as 2004.

As she drew closer, though, the message was amplified. This will surpass 2004. This will be 1916 all over again. Those old photos were shared in media as warnings.

The National Weather Service Greenville-Spartanburg office sent dozens of warnings. One of the last ones I saw came out the night before and sent chills down my spine:

What we hadn’t expected was that it was going to be far worse than anything imaginable.

The Pre-Helene rain

To understand why things were so bad, start with the days before Helene. It rained. A lot. As so often happens in these mountains, a storm system stalled and dumped water on us.

Helene’s approach pinned that other system against our mountains. A drenching, soaking rain flooded all the usual spots.

We last ventured from the house on Wednesday, September 25, for dinner at a local restaurant. Our return trip home was very slow because flooding had reduced the interstate to one lane.

A meeting we had scheduled for Thursday morning was canceled because of the weather. Heavy rains and a few fallen trees made travel too difficult. Rivers and creeks floated at minor flood levels.

Hidden in the forests surrounding us on mountain ridges, the ground became saturated.

Helene arrived Friday morning.

Wind

Our mountains get wind. Some serious wind. Trees sometimes go down. It happens. It’s mountain life.

But Helene’s winds howled. Sassafras Mountain saw a 73 mph gust. Frying Pan Mountain recorded an 87 mph gust. Mt. Mitchell, always our weather extreme, clocked in 103 mph.

If it had been dry, most of the trees would have held. They had felt such winds before.

But the ground was soaked. The roots didn’t hold. Trees fell. One after another. In town, they tumbled across power lines, streets, and houses. Our giant walnut tree came to rest on top of our roof, though we had far less damage than most people. Many of our neighbors had trees crush through into the rooms below.

The worst was happening out of sight. Because communications of all sorts collapsed, we had no way of knowing. Entire forests along the ridges gave up their grip and slammed to the ground. Trees fell in waves by the thousands. Their root systems no longer held the dirt and rocks in place.

The disaster was set, but needed just one more element.

More rain

Helene poured water on us. An absolute deluge came falling from the sky. The community of Busick recorded an astounding 30.78 inches of rain in the four days surrounding Helene. The ground couldn’t absorb another drop. The water had to go somewhere.

Gravity answers the where—downhill. Thanks to those uprooted trees along the slopes and ridges, the water flowed unobstructed. It picked up the loose dirt and rock in its path.

Anyone who has ever seen a snow avalanche knows how it works. A trickle of snow picks up more snow. Clumps become gigantic walls of snow.

A debris flow is euphemistically known as a mudslide, but that so misleads what’s in the debris. Water, mud, rocks, trees, and anything else in its path become of a part of the cascade. Slides merge, forming massive waves hurtling down the mountains.

Trees snap in the path. Houses are ripped off their foundations and are splintered into toothpicks. Cars, people, and animals are encased. Each object is added to the material in the flow.

It stops only when it hits flat ground or a river bed. In the mile or two before that happens, everything in its path is destroyed.

The US Geological Survey is mapping each slide and currently counts nearly 2,000, with many more yet to be discovered. Some ended harmlessly. Others destroyed infrastructure by burying roads, railroads, and power poles, or ripping the ground from underneath them. The most devastating slammed into homes and businesses.

The ancient Swannanoa Mountains to the east of Asheville produced one of the most tragic combinations of slides. They merged and slammed into the tiny community of Craigtown, killing 11 members of the same extended family.

Two fire fighters valiantly digging through the destruction in search of victims were trapped when another wave of debris crashed over them. They couldn’t move out of the way fast enough as the killer raced down the mountain and buried them.

Asheville Reservoir

Near Swannanoa, this fresh water reservoir is normally crystal clean, provides water to most of Asheville, and supplements several surrounding water systems. The flooding of 2004 destroyed both the main water supply pipelines from the reservoir. To prevent that from every happening again, the city added a third line and buried it 25 feet deep. By itself, that 36 inch line could provide the city if the other two were destroyed.

It wasn’t enough. Those debris flows took out all three lines and filled the reservoir with literal mountains of mud and rocks.

That third line has since been rebuilt (the other two are underway), but the sediment in the reservoir hasn’t yet settled. Until it does, the sludge would just clog the treatment plant, so it must bypass it. That’s why we still don’t have drinkable water.

The Floods

Which brings us to the simplest to understand and most deadly consequence of the storm. The saturated ground meant that water had nowhere to go but into the rivers. The landslides opened the path for the water to hit the rivers even faster. Worse, they filled the beds raising the levels even higher. Lumber, cars, and entire houses floated on top, deadly missiles ready to destroy anything they collided with.

The rivers rose past 2004. Beyond 1916. And ever higher than 1791.

People didn’t ignore warnings. They genuinely thought they were high and safe enough. They didn’t discover the truth until it was too late. Those who survived made it out with little more than the clothes on their backs.

In some places, those rivers run through urban areas like Biltmore Village and the River Arts District in Asheville. In others, they flow through isolated gorges like Bat Cave and Chimney Rock. These are the scenes of destruction you have probably seen.

The Aftermath

The city and region will come back. Different, but we’ll be here.

Many of the smaller communities sheltered from the worst are already functioning and welcoming the critical economics of tourism. Restaurants are reopening. The Biltmore House will welcome guests for the first time since Helene this coming Saturday. The DOT is working on plans to rebuild Interstate 40 through the Pigeon River gorge and into Tennessee.

How you can help?

But some people and some communities will never be the same. They need your help.

I listed some organizations in an earlier social media post and will repeat them below. These are terrific groups working hard to help the people in our area. As you plan any year-end charitable gifts, consider these groups. Many, many legitimate organizations deserve a spot on the list, but I can’t list them all.

But I also urge you to think of your upcoming holiday spending. Consider ordering gifts from the many artisans and family businesses in our mountains. Even if you can’t visit, you can order online from many of these places. And certainly plan a family vacation to the areas that are open (and many are) and support those local businesses with your tourism dollars.

Manna Foodbank has been a critical link in food support for years. Their warehouse was destroyed by flooding, but they have already opened a new warehouse and resumed their important work.

Love Asheville from Afar – Consider doing your Christmas shopping or donating to this list of local businesses hammered by Helene.

The Community Foundation of Western North Carolina – Funding grants daily across the region to support the smaller organizations providing direct support.

Asheville Area Habitat for Humanity – Their good work in building houses for people in need will be critical to recovery for those who lost everything without flood insurance (which very few people here carry).

Brother Wolf Animal Rescue – A long-standing animal rescue that lost their facility and vehicles in flooding. Fortunately, they housed all their animals with volunteers prior to Helene’s arrival, but they are working to rebuild.

Support The Musings

Call it a tip. Or the euphemestic "Buy me a coffee." I prefer patronage. Generous patrons have supported artists throughout history man. Whatever you want to call it, if you enjoyed this post, consider making a donation to help offset my costs. Your support will help keep my stories ad free. Click here to make a contribution of any amount.

6 Comments

Leave a Comment

Monthly Reader Survey

Each month, I ask my readers a question or two. Sometimes, my questions are random fun things that have nothing to do with books. Other queries are about reading and writing. Join in the fun and answer this month's survey. The results (and a new survey) will be shared later in the month.

Monthly Reader Survey

Each month, I ask my readers a question or two. Sometimes, my questions are random fun things that have nothing to do with books. Other queries are about reading and writing. Join in the fun and answer this month's survey. The results (and a new survey) will be shared later in the month.

I can’t really comment, I’m an old lady living in a part of suburban Sydney, Australia that is relatively safe from weather related disasters but your graphic descriptions and the one photo make it quite clear just how bad things were. Last year I was driven through a part of New Zealand still recovering from a similar event caused by rain. Not as bad on a comparitive scale but terrible enough and I cried to see the destruction, fields deep in mud, bridges destroyed by trees which were washed down the rivers then out to sea and back again on to the beaches by the tide. Nature can be very powerful and very cruel.

Now it’s so much easier to understand how Helene could have caused that amount of destruction realizing how the mountains were battered with rain and wind to cause chaos, flooding and damage. Thank you for your thoughts!

Thank you for a great recap of the tragedy. I truly appreciate it.

https://www.facebook.com/mountainmulepackersranch/ has had boots and mules on the ground the whole time helping when FEMA could not be found. They are another great place to donate to because they are showing everything they are doing to help.

Thank for sharing, some of who read you, were worry and sad while news were reporting. You are blesed.

From where some of your readers are (like me) probably it is only comparable with earthwakes, but this year at same Helen happens we were dealing against worse forest fire and of course were not prepared, and were helpless spectators of the loss of our precious amazon forest. These events remind us that we really need to respect nature, and try to mitigate a little (at least) the irremediable climate change.

Great summary, Kirk. Thanks for pulling all this information together in such an accessible way. It’s still hard to read (though Mac and I are delighted to have gotten power back a little over a week ago!). It was still scary hearing the winds on top Mt Leconte last night even though they were only 15ish mph. I suspect some of these reactions will last for quite a while.