Share This Musing

This time last year, we were dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Isaias—fallen trees, flooding, alligator burglars, and social media scorn.

Isaias wasn’t the worst hurricane—unless, of course, you were a meteorologist forced to pronounce the name on live TV. We all mangled the name until it became obvious we were going to have to deal with it. Soon enough, we learned.

Hurricanes are weird creatures. You know they are out there for days and days before they approach, like a maniacal, relentless turtle bearing down on you. That might make a good 1960’s horror movie, but it’s no fun to live through.

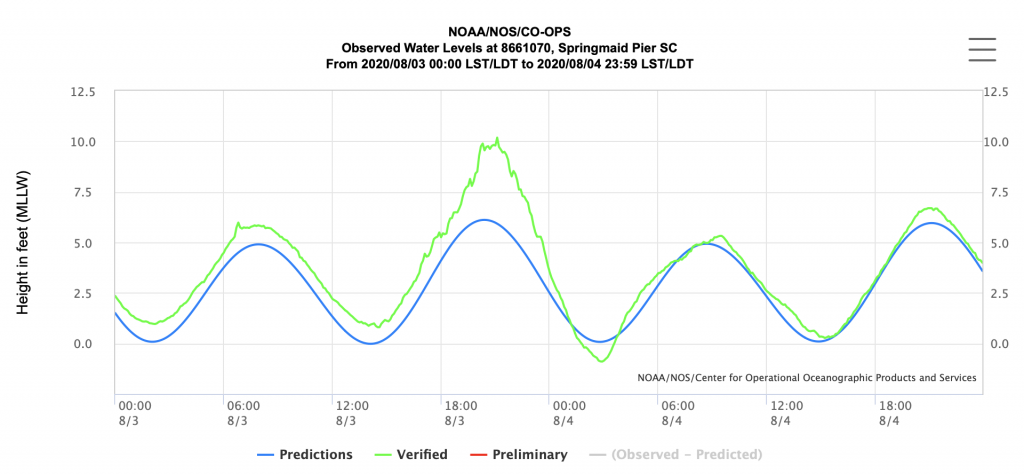

Unlike Hurricane Dorian the year before, we weren’t faced with mandatory evacuations (which we ignored like most locals did). The storm was never expected to be particularly strong. If it had come ashore when it was predicted to, it probably would not be remembered much at all. Instead, it hit hours later than we were prepared for after nightfall right at the time of the high tide. The timing couldn’t have been worse because it was also the day after the full moon (the highest tides of the month) in August (the highest tides of the year). The chart below sums things up:

The ultimate cruel joke is that the storm moved away from us in time for the low tide early the morning of August 4th. When a hurricane approaches, it pushes a wall of water at land. When it moves on, it sucks that water back out to sea. Note that the low tide was lower than normal the morning after, which made for a weird sight out over the marsh,

Shortly after dark the night before, though, a 10.18 foot high wall of water, the third highest tide ever recorded at the official measurement point for Myrtle Beach, came ashore. Only Hurricanes Hugo and Matthew had higher tides. (Hurricane Hazel happened prior to those records being kept, but it would be on the list as well since it also hit at the lunar high tides of October 1954).

We sat in our house in Murrells Inlet that evening, at first relieved that the storm didn’t seem so terrible. The rain was steady, the winds strong, but nothing indicated it would be bad. The water in the marsh, though, rose and rose. We watched it creep up to the fence. Then inside the yard. Then over the pool. And then to the house.

People out on the barriers were dealing with waist-high water, so they had it far worse. We, fortunately, had a mess, but we were safe and, in the house, dry. Since our house sat on stilts ten feet above the ground, we were never at risk. Other than having to clean the pool and yard of debris, we had no damage.

During the height of the storm, my phone pinged with a text. Our neighborhood had a group chat going, as we did in every hurricane. If anyone had damage or was in trouble, neighbors came running to help. We looked after each other. So when my phone pinged, I grabbed it. This is what I saw:

Yes, an alligator had taken refuge from the storm under their house (note you can see the waterline on the walls, so the water was already receding). The poor guy had been blown off course. We lived in a salt marsh. Alligators prefer fresh water. They will come to salt water for food, but they don’t stay there. He simply wanted shelter until he could safely work his way back to fresh water.

After several texts back and forth, we agreed everyone was safe. The gator could stay until the weather calmed. Sure enough, by daybreak, he had moved on to more hospitable ground. Unfortunately for me, I posted the following fateful item on Facebook, not a particularly hospitable place:

Hurricane threats you don’t think of. A neighbor is reporting a confused alligator took refuge from the hurricane in her basement. Uh. No.

During the night, I posted many things. Pictures of flooding. Videos of howling rain and wind. Observations that struck me as funny (because my weird mind finds many things funny). None of them received as much attention as that post. Not because of the alligator. Because I said basement.

A basement in Murrells Inlet??? I have never heard of a basement around here.

Over and over, I was told the same thing. In typical social media fashion, the experts piled on. My sanity was questioned. My intelligence. Not because I stayed in my house during a hurricane, but because I called the space below it a basement.

Coastal houses are built on stilts. In our case, like many others, there is a lot of distance between the bottom of the living quarters and the ground. They are enclosed with slats, plenty of open space for water and air to flow, but secure enough. We parked out cars there. Stored tools on hooks on walls. Certain mechanical equipment hung from the ceiling. We had steps from the main floor to the ground inside. It was secured with locking doors.

The post was shared, probably because of the mention of the alligator, but more people piled on. Then I received this comment:

I have been in real estate for 21 years and we have never identified the area under a raised beach house a “basement”.

Great. A learned expert, despite the misplacement of the period outside of the quotation mark, but I would be pedantic and petty to point that out. Over two decades of real estate experience. I love language. I love learning new words. And so I asked, what do you call it? The answer was less than satisfactory:

It doesn’t have a definitive name that I have ever heard used. It is usually parking area or space used for outdoor entertainment.

Yeah, because that’s much easier to say and clearer than basement. But if a two-decade long experience in real estate didn’t illuminate the answer, what did? So I set off on a quest.

I asked neighbors. I asked long-time coastal residents. I asked contractors who had been building coastal houses on stilts for decades. What do you call the space? Most people looked at me like I was nuts (a not unusual experience). Most agreed it wasn’t a basement, but they had no idea what to call it.

I hit the books. What does Merriam Webster say? The first definition is the one everyone thinks of:

The part of a building that is wholly or partly below ground level

But, wait, what’s the second definition?

The ground floor facade or interior in Renaissance architecture

The main floor, piano nobile, of renaissance structures was often one level above the street. The ground floor was used for various mechanical or storage reasons, but the living floors started higher. Doing so allowed the living quarters to be above the noise of the streets outside. It also allowed them to avoid flooding. The space below was referred to as ground floor or—wait for it—basement.

I remember well my first trip to Europe and discovering the “first” floor referred to the first floor above the ground floor, what we Americans would call the second floor. Imagine my confusion on an elevator when the first button was marked 0. And, yet, it makes sense.

The style was replicated here in the U.S., particularly in large colonial era homes. Think of the sweeping staircases rising from street level to a front porch and the front door. The space below was used for storage.

By the way, another interesting learning as I dug through this—The primary difference between a basement and a cellar is that a basement is full height and often has windows, while a cellar tends to be shorter and fully underground. In fact, we often use the term “daylight basement” to refer to a lower floor that is, at least partially, above ground.

So here I am a year later, safely ensconced back in the mountains well away from storm surges. We have in this house what was marketed as a basement, with its own entrance at ground level. We’ve sold the house in Murrells Inlet. And I still haven’t found a universally accepted answer of what you call the ground floor at the coast.

Until then, I’ll stick with basement. I’m okay with social media scorn.

Books Read

John Hart depicts life in the Piedmont of North Carolina like no other author. I hadn’t read his 2010 novel and am glad I backtracked to do so.

Work Pickens isn’t much of a likeable protagonist. He’s a middling lawyer who hates his job and barely makes a living. His wife is a gold-digging socialite who tolerates his affair with another woman. His relationship with his sister is strained, not helped by the open animosity from her lover. Mostly, he anesthetizes himself with booze and cigarettes to get through the day.

His main claim to fame is his partner, his father who is a a legendary and ferocious lawyer who isn’t liked by very many people. When the elder Pickens’ body is discovered, two years after his disappearance, with two bullet holes, the whodunit begins.

For Work, the suspect is simple—his sister. She has plenty of reasons to hate their father, but Work wants to protect her anyway he can. Since he is the second most-likely suspect in the police’s eye, it’s easy enough to distract them. Soon enough, though, things spin out of control as everyone becomes convinced Work really did commit the crime.

As the reader is exposed to Work’s past through a series of vignettes, it’s easy to suspect he did do it.

After the initial building of all of the characters, the novel moves rapidly to its revelations.

Interesting Link

A Triune Tale of Diminutive Swine –Comedian John Branyan shares his version of The Three Little Pigs—as if William Shakespeare had written it. If you’ve never seen this rendition, it’s well worth a few minutes:

Gratuitous Dog Picture

I am often asked why I refer to His Haughtiness as His Royal Highness Little Prince Typhoon Phooey. Really, just look at him. He’s handsome. He knows it. And he really doesn’t care what mere humans might think.

Support The Musings

Call it a tip. Or the euphemestic "Buy me a coffee." I prefer patronage. Generous patrons have supported artists throughout history. Whatever you want to call it, if you enjoyed this post, consider making a donation to help offset my costs. Your support will help keep my stories ad free. Click here to make a contribution of any amount.

5 Comments

Leave a Comment

Monthly Reader Survey

Each month, I ask my readers a question or two. Sometimes, my questions are random fun things that have nothing to do with books. Other queries are about reading and writing. Join in the fun and answer this month's survey. The results (and a new survey) will be shared later in the month.

Monthly Reader Survey

Each month, I ask my readers a question or two. Sometimes, my questions are random fun things that have nothing to do with books. Other queries are about reading and writing. Join in the fun and answer this month's survey. The results (and a new survey) will be shared later in the month.

Hu-Dad I have to say I have been SO engrossed in today’s post. The BASEMENT story is really interesting. Since we have never lived on a house built on stilts and then having a covered area to park etc really was something! I would probably call it a basement too because that’s what I grew up with.

The John Branyan video had me laughing hearing the 16TH century rendition of The 3 Little Pigs too!

Finally of course Typhoon is a royal-just look at him-totally a PRINCE!

A lot of good reading and watching today. (John Branyan is like a clean George Carlin. We’ll be watching more of him.) Also learned a new word, pedant, which I guess we’ve referred to as grammar cop. I’m now thinking if my punctuation is correct. :-))

Typhoon is looking very regal in that shot.

I am just call mine a cellar and never thought about it! Will check out that book, thanks. Typhoon is really handsome today.

Idk. I tend to think of a basement as a completely enclosed, at least partly underground space. But really, who cares?

I suspect you may be better off in the long run in NC. It’s quite possible that the property you lived on in SC will be underwater in 10 or 20 years. Maybe not very far underwater, but still.

I agree with you. If you had asked me before Isaias what to call that space, I probably would have reacted the same as everyone else—”I don’t know.” It just tickled me of all of the things I posted during the course of a hurricane, that was the item I took grief for.

And, yes, we are quite happy to be back in our beloved North Carolina mountains. We love the coast, but decided we’re more suited for visiting it than living there.